(a talk given at Sunday Assembly Atlanta, Oct 16 2016)

So I want to talk about ideas, collaboration, progress, and libraries. I believe that to maintain and improve civilization, we (that is, everybody) must create objects of communication that express our ideas, values, beliefs, and aesthetics in an accessible, discoverable, and preservable way. That used to be books, mostly, or variations on books, but in the past 150 years, ever since electricity entered the mix and made this glorious disaster that is modern life, the ways we create, access, discover, and preserve these “objects of communication” have multiplied and become easier.

It’s a conversation because the flip-side of creating objects of communication is to observe and respond to objects made by others. I’m calling that the Conversation of Civilization, because I like alliteration and grandiose claims.

Here we go:

I. Where do you get your ideas?

A question that invites sarcasm

It’s a question for writers, mostly, but a fair question for everybody. And most of the time, writers make jokes about where they get their ideas: off the back of a truck, through a mail-order service, from a fella in a blue trench coat, every Thursday.

The jokes often hide a near-superstitious fear of the “drying up” of ideas. We all know that ideas come at odd times, like in the shower or on a walk, or as a response to something that is happening that seemingly has nothing to do with the idea we have. What many of us don’t know, or don’t want to think about for fear of disrupting the process, is how we get new ideas.

So let’s talk about how a few people have understood or handled ideas.

II. Dr. Asimov Declines, Respectfully

The question of creativity circa 1960

Dr. Isaac Asimov was a chemist and writer of science fiction, mysteries, popular science, and histories.

Years ago, Isaac Asimov was asked to take part in a project. Here’s Arthur Obermayer’s description of the project:

In 1959, I worked as a scientist at Allied Research Associates in Boston. The company was an MIT spinoff that originally focused on the effects of nuclear weapons on aircraft structures. The company received a contract with the acronym GLIPAR (Guide Line Identification Program for Antimissile Research) from the Advanced Research Projects Agency to elicit the most creative approaches possible for a ballistic missile defense system. The government recognized that no matter how much was spent on improving and expanding current technology, it would remain inadequate. They wanted us and a few other contractors to think “out of the box.”

When I first became involved in the project, I suggested that Isaac Asimov, who was a good friend of mine, would be an appropriate person to participate. He expressed his willingness and came to a few meetings. He eventually decided not to continue, because he did not want to have access to any secret classified information; it would limit his freedom of expression.

Before he left, however, he wrote this essay on creativity as his single formal input. This essay was never published or used beyond our small group. When I recently rediscovered it while cleaning out some old files, I recognized that its contents are as broadly relevant today as when he wrote it.

So the essay is from 1959 but unpublished until 2014. Asimov lays out in a very engineer-like way the requirements for getting new ideas about a problem and getting people to work together. It is a great essay in a lot of ways, and it is also hilarious if you contrast it with the way people talk about creativity now.

To summarize: get a bunch of people who are experts on a variety of fields, who can speak to each other informally and without judgement, who are a little weird but in a good way, and let them talk about the problem with each other. Then they’ll go away and come up with ideas on their own.

This photo is titled “Isaac Asimov Hails a Cab.” Look at him. He’s fantastic.

He said that coming up with ideas is a solitary process but getting your head to a place where you could come up with ideas was a group activity:

“It seems to me then that the purpose of cerebration sessions is not to think up new ideas but to educate the participants in facts and fact-combinations, in theories and vagrant thoughts.”

Facts and fact-combinations! Hilarious. Asimov made it almost mathematical how you can come to new ways of thinking: if I know A-B, and you know B-C, then together we might talk until we discover A-B-C.

Now, A-B-C is not a new idea. It’s a new fact-combination for us, it’s a new thread of thought. And then A-B-C might influence ideas we both have.

So let’s get back to where ideas come from.

III. David Lynch is a Fisherman

In which we consider a metaphor

David Lynch is a filmmaker and an artist. He directed Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Lost Highway, The Straight Story, Mulholland Drive, and the television show Twin Peaks, along with many others.

David Lynch is a known expert in a field (Oscar-nominated director and screenwriter), and he is a little weird in a good way. He was an Eagle Scout, did you know that?

I adore David Lynch, for many reasons, and one of them is a documentary about him called Pretty as a Picture: The Art of David Lynch, where he delivers a lot of his artistic philosophy in a folksy way.

That was the place where I first heard his metaphor for ideas. It’s a water metaphor. Ideas bubble up, he says, and you can grab them.

From where? How? Why? “Who cares?” is the answer for a working artist like Lynch, I think.

But what he does care about is getting to a place, mentally, where the ideas can bubble up. Or, as he eventually got to metaphorically, where you can catch the big fish.

“Ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper.”

from Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity, 2006

The deep water is a nice bit of poetry for your mind, describing the way it feels when you remember something and another something and then suddenly you’re thinking something you never thought of before. The deep water is full of facts and fact-combinations, swimming around and eating each other, and getting bigger and bigger and bigger. Or something like that. This is not an allegory.

IV. Thomas Edison was a Machine

The difference between work and ideas

Lynch is an artist, and he’s trying to plumb his unconscious for images and relationships that make psychological sense, not engineering sense. Thomas Edison, on the other hand, was trying to patent inventions that would sell.

Why am I talking about Edison? Well, what’s the classic symbol for an idea?

And I love the irony. We use the lightbulb to signify an idea: the flick of a switch and illumination. And the person we think of as the inventor of the lightbulb did not come up with the idea, not by a long shot.

This is an incomplete list of individuals who contributed to the invention of the lightbulb:

- Alessandro Volta

- Humphrey Davy

- Warren de la Rue

- William Staite

- Joseph Swan

- Charlie Francis Brush

- Henry Woodward

- Matthew Evans

- Lewis Howard Latimer

- Willis R. Whitney

- William David Coolidge

- [The women who should be on this list have been hidden by history]

All these people worked on and talked about what would eventually be the lightbulb. They were all parts of the chain of facts and fact-combinations that would eventually lead to

the way that Thomas Edison did things — grinding through all the possibilities like a good engineer. Woodward and Evans sold a patent to Thomas Edison, and then he and the team at Menlo Park tested 3000 designs.

Edison scooped up ideas that had been sent out into the world, as patents, as art, as prediction, and applied a method to those ideas until he got a result that worked for him.

Now it’s very cool and hip to say that Nikola Tesla was an inspired genius and Edison was an opportunistic businessman but I haven’t done the research to confirm for myself if that was really the dichotomy between the two. I just wanted to bring up Tesla so I could segue to talking about radio.

V. The Enchantments of Radio (and podcasting)

In which I get personal

I started a radio show with my friend Ameet in 2010, and I have been hooked ever since.

Radio, as a practice, is everything I like to do and nothing I don’t. You speak in a controlled environment, without anybody looking at you — you control a single sense and everything else is up to the listener. My radio show, Lost in the Stacks, is a show about library and information science with rock & roll in it. For an hour, we broadcast music and library talk, all organized around a new theme each week. We make fact-combinations that include librarian in-jokes and blues-rock.

Which is cool, but our ideal audience is scattered throughout the world, and we’re on a local Atlanta radio station.

Audacity, the sound-editing program I use to cut all my podcasts.

Then I discovered podcasting, and there was nothing to stop anyone from listening to me. The listener could download an audio file whenever, to be heard whenever, almost anywhere.

And with the minimal obstacle to entry, you can experiment with the form — conversation podcasts, interview podcasts, narrative or collage podcasts. I enjoy them all.

So this practice of broadcasting and podcasting, where does it connect to this talk?

The end credits for Mystery Science Theater 3000

This is my object of communication. The audio file — downloadable, transferable, copyable, mostly convenient. Every week I spend 3 to 5 hours working out what I think and why I think it, about all kinds of subjects.

It has been an extraordinary period in my life. I have felt more productive and connected to the world than ever before. The Internet helps, of course, but the weekly practice of communication has been remarkable.

VI. A Call to Action

Live better, help often, wonder more, tell your story

On a non-commercial radio station, such as my beloved WREK Atlanta, we are not allowed to deliver calls to action on air. You can’t tell people to buy a hamburger, you can’t tell them to vote, you can’t even suggest that they step outside and get some fresh air.

But here, in a different venue, I’m all about a call to action.

Begin a practice of communication. Articulate your story, your values, your facts and fact-combinations, in a way that gives you the raw material you need to develop some object of communication.

If you’re already creating the raw material, then kick it up a notch and make those objects of communication. Establish an activity that you must do weekly — something that you have to go out of your way to do, and something that people come to expect. An audience that asks you why you haven’t produced the next iteration of whatever is your weekly communication will seriously motivate you to complete your work.

We have so many ways to communicate available to us, and the Internet makes distribution pretty simple. I’m sure all of you can come up with a practice and a method of distribution that is yours, completely, so I don’t want to spoil your ideas with stupid examples.

VII. Hey, Aren’t You a Librarian?

Bringing it all back home

Okay, coming in for a landing. Why am I telling you all this? Why did I just suggest you start a zine or a collage of the week club? (See, stupid examples.)

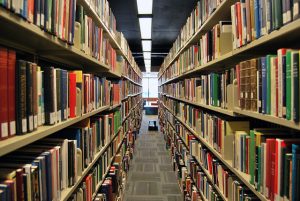

I am a librarian. And I have a particular view of libraries.

Isn’t that beautiful? Look at all those fact-combinations. Each of those books represents a careful construction of an argument — a pulling-together of work and references into an easily accessible form. I’m guessing there’s about 5000 books in this picture, which could easily represent six thousand years of work, which is, coincidentally, the age of human civilization. So that’s one civilization worth of books.

I am a bibilophile, and certainly I will always advise that you read all the books you can, but that is not the only purpose of libraries.

I have said many times before that libraries are not collections of books — they are where we store the intellectual and creative output of a community, in whatever form we produce it.

And those forms are increasingly digital — or increasingly distributed digitally.

So maybe this is the library, too.

Whatever form the library takes, all of us are producing the work that it should collect. You don’t have to be a published author for the library to preserve your work and make it easy for others to find it. And I will fight any librarian who insists that the collection must comprise only mainstream, vetted, universal material.

The library is full of all those facts and fact-combinations that Asimov was talking about — this is your stash of new stuff for your head. You don’t get your ideas out of the library — you get the raw material for ideas. And then those ideas go through your practice of communication, end up back in the library, and become the raw material for someone else. This is the conversation of civilization. We should all take part.

Where I Found Things

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/zzazazz/2264043946

- https://www.technologyreview.com/s/531911/isaac-asimov-asks-how-do-people-get-new-ideas/

- http://www.indiewire.com/2013/02/video-essay-beautiful-nightmares-david-lynchs-collective-dream-133858/

- https://www.davidlynchfoundation.org/catching-the-big-fish-meditation-consciousness-and-creativity.html

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/Incandescent_light_bulb.svg/2000px-Incandescent_light_bulb.svg.png

- https://li.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Edison#/media/File:ThomasEdison.jpg

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/dvortygirl/2445114424

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/xiaozhuli/4148490085

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6610372